I'm a paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

Another Global Debt Crisis May Be Coming Soon

Global debt crises are a recurring event in capitalism. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, both prominent Harvard economists, published a masterpiece in 2011: This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. (Princeton University Press). This Time Is Different showed that historically, there have been consistent global financial crises that occur every thirty to forty years. Before the crises, banks in the rich country make loans to the poor countries. Early on such loans are generally sustainable. However, the volume of loans increases and increases beyond the capacity of the poorer nations to meet their obligations. The over-lending comes from misplaced optimism on the part of the banks. It also comes from inappropriate incentives to close deals because international loans generate large and lucrative closing and syndication fees. The banks collect the fees Day One. Repayment problems don’t occur until ten to twenty years later. The individual bankers responsible for creating massive financial problems are rarely around to face the consequences of their actions when the loans go sour.

When the defaults come, the economic consequence are dire. Economic growth tanks in the Global South and in the world in general. The stagnation is far worse in the poor countries than it is in the wealthier countries. Everyone in the world suffers somewhat. The economic losses in the Global Periphery are so severe that the decades of debt crisis are often sometimes referred to as “Lost Decades”.

One of the greatest global debt crises was in the 1980’s. It began with Mexico having to default on its debt in 1982 – a default which led to a worldwide financial panic that led to parallel debt crises in Latin America and Eastern Europe. It took ten years for growth to return to these regions.

We may be on the road for the same thing to be happening again.

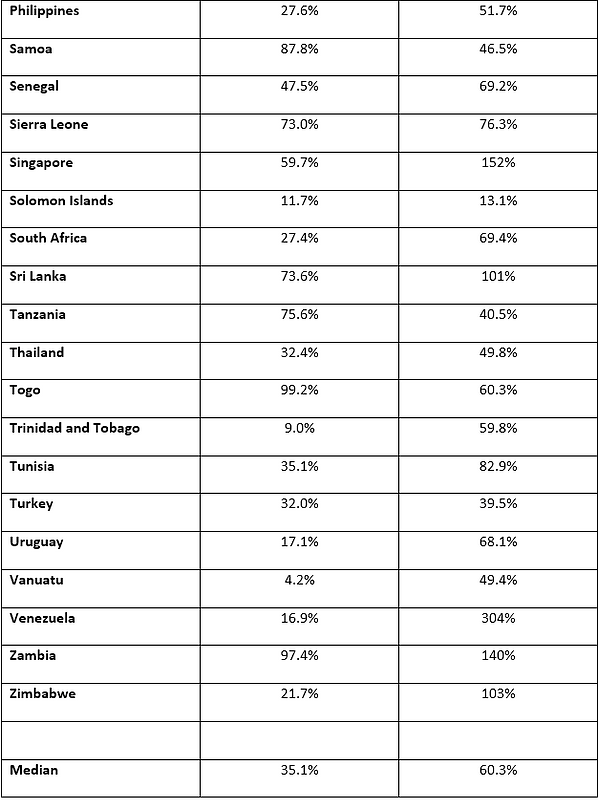

The table below lists the ratio of public debt to GDP for the non-petroleum nations in the Global South in 1981 and 2020. The poor countries in the world are looking at a far larger public debt burden relative to their economies than existed in 1981 just before the 1982 financial collapse.

Ratio of Public Debt to GDP 1981 and 2020

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

Sources: 1981 International Monetary Fund Historical Debt Database; 2020 IMF World Economic Outlook Database en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_public_debt

How bad is the bad news on this table?

Globally, Debt/GDP ratios nearly doubled. In 1980, the median Debt/GDP was 35% Now it is 60%.

However, it only takes a small number of defaults to topple a global system. Look at three of the nations who had major debt issues in the 1980’s Latin American Meltdown.

In 1980, just before the Global Debt Crisis, Argentina’s Debt/GDP ratio was 21%. Today it is 103%.

In 1980, Brazil’s Debt/GDP ratio was 34.8%. It is now 98.7%.

In 1980, Uruguay’s Debt/GDP ratio was 17.1%. It is now 68.1%

Things get worse.

In 1980, only two nations had Debt/GDP ratios above 100%: Bolivia and Costa Rica.

In 2020, twelve nations have that dubious distinction. Some of these involve economies that are well known to be problematic – such as Venezuela. One is a cornerstone of the world economy: Singapore.

Twelve nations have seen their Debt/GDP ratio double or more than double since 1980 – while currently having debt ratios higher than 75% of their GDP. 75% is a worrisome number. Some of these nations are small, like Dominica. Some of these economies are major, such as the aforementioned Argentina and Brazil – but also India. India’s Debt/GDP ratio is over 90%. (Just for the record, Pakistan is nearly as bad off, being at nearly 80%) A financial collapse in India or Pakistan could easily have global ramifications. Don’t even start thinking about the geopolitical or ethnic ramifications if domestic economic problems induce leaders in either nation to scapegoat the other country – or in the case of India – the Moslem population within their borders.

Hopefully, I am just being a worry wort. Nothing bad is going to happen, and the global economy will just keep on progressing smoothly. But the historical record cited by Reinhart and Rogoff is somewhat disconcerting. The world regularly over-lends to the Global South. The Global South regularly crashed because of such over-lending.

Could history repeat itself here? The current indebtedness statistics are not comforting.